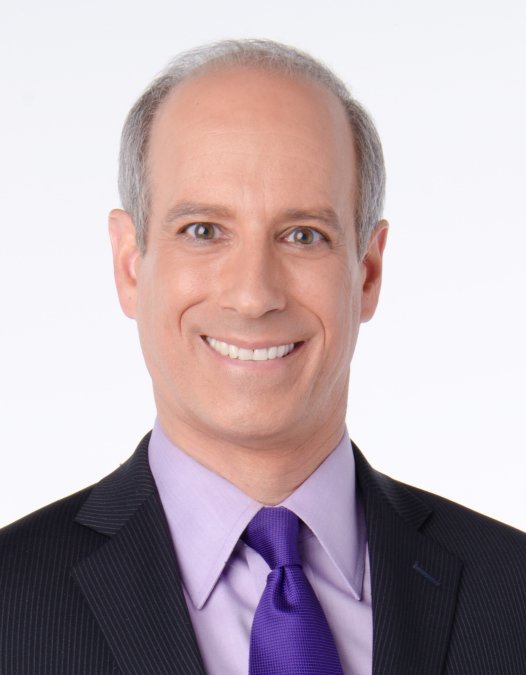

After graduating in 1983 from the University of Michigan with a bachelor's of science degree in atmospheric science, Gross went on to work as a broadcast meteorologist at multiple television and radio stations across Michigan and in Canada throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s, including at WDIV-TV, the “Channel 4” station he and his family watched in his youth and where he currently works today.

In addition to standard weather reporting, Gross goes out of his way to incorporate broader science reporting into his coverage, walking the talk that earned him six Emmy awards and led him to become the chair of the American Meteorological Society’s Committee on the Station Scientist for seven years. Aside from his work in broadcast media, Gross is also a certified consulting meteorologist, using his scientific background to testify as an expert meteorologist in court.

What kinds of math, science, engineering, or technology classes did you need to take in school to prepare for your current career?

Paul Gross: The University of Michigan meteorology program required seven semesters of math (the first three were calculus, there were then four more after that), three semesters of chemistry, two semesters of physics, engineering dynamics and fluid mechanics, two courses of atmospheric dynamics, atmospheric thermodynamics, radiative transfer in the atmosphere, synoptic meteorology classes, and others that I can’t remember at this moment. Keep in mind that, unlike most universities, the meteorology program at the University of Michigan is in its prestigious College of Engineering.

How are weather forecasts created? How do computers factor into creating these forecasts?

PG: It starts by “looking out the window”– checking radar and satellite images, upper air data, surface observations, etc. to see what’s happening now. This sometimes includes hand analyzing a regional surface analysis, which very few people do anymore. I then look at the various computer models to determine what’s causing the weather over us or heading our way. I then evaluate which models have the best handle on those features of interest and their movement and evolution. Once that decision is made, I then start writing down specifics of my forecast.

The computer models are vital today. They model atmospheric motion and physics in such a way that we meteorologists have a wealth of scientific guidance to consider when making our forecasts. Prior to computer models, there was a much greater emphasis placed on experience and those hand-analyzed maps. Those are still important to ME even today due to my personal forecast process, but the computer models give me a critical added element that allows me to forecast much more accurately, with much more detail, and farther into the future than I could have possibly dreamed when I started my career.

Is there a specific breakthrough or event in your field’s history that stands out to you as a milestone? Why would you say it is so important?

PG: I can’t choose just one, because many developments were so vitally important at that time. I don’t know how far back you want to go, but Vilhelm Bjerknes’ development of the cyclone development theory and fronts changed what meteorologists saw and tracked on surface maps. The modification of military radars to use with weather was a critical development. So was launching of weather satellites…for the first time, we saw things like evolving storm systems, as well as hurricanes well before they got close to land. The advancement in computers, which allowed the development and use of numerical weather prediction (i.e., computer models) was obviously very important at that time. One of the most important developments was exploitation of the internet–all of a sudden, weather information could be shared and accessed more easily than ever before. Believe it or not, I can now forecast the weather as accurately at home as I can at work. How do I choose among these? Each was such an important advancement in meteorology at that time.

What would you say has been your proudest accomplishment on the job, or your favorite part of the job?

PG: Three accomplishments that I cherish equally:

- In the late 1990s, I was made aware that there was nothing in State of Michigan law requiring public schools to conduct tornado safety drills. I contacted a state legislator who agreed, he introduced a bill, I testified about the tornado threat here in Michigan before a State House and, later, Senate committee, and was with the governor when the “Gross Weather Bill” was signed into law.

- Back in the early 1990s, I spent three and a half years researching and gathering interviews about the weather and how it impacted D-Day in World War II, and my documentary [Forecast: Overlord] was deemed so historically significant that it was added to the official D-Day archives at the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, the Museums of Television and Radio History in New York and Chicago, and the British Meteorological Archives.

- More recently, I have succeeded in earning the trust of my viewers with updates and reporting about climate change, to such a degree that my news director now asks me to do MORE of it. How many of my colleagues can say that?

Additional sources:

- Click on Detroit. 2015. "Paul Gross." Graham Media Group. Accessed April 12, 2016. www.clickondetroit.com/news/paul-gross

- Paul Gross. 2016. "PAUL H. GROSS, C.C.M. CERTIFIED CONSULTING METEOROLOGIST." Accessed April 12. http://grossweather.com/resume.html