A conversation with Terrence Williams, Principal at Benjamin Franklin Middle School in Teaneck, New Jersey

Terrence Williams is an educator with over 20 years of instructional and leadership experience in elementary, middle, and high school settings. He specializes in student-centered, inquiry-based education that prepares students for success in the 21st century. A three-time graduate of Rutgers University, Terrence has also earned a Certificate in Advanced Education Leadership from Harvard University's Graduate School of Education and is currently pursuing a doctorate in educational administration and supervision at Penn.

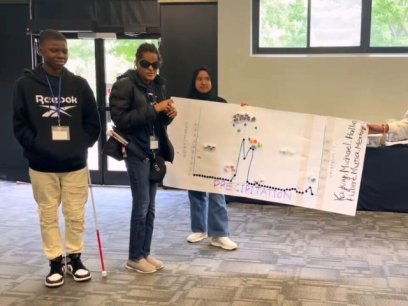

As the Principal of Benjamin Franklin Middle School, the school partnered with NEEF, Samsung Electronics America, and the Teaneck Creek Conservancy for a demonstration of the Greening STEM approach. From March 11-12, seventh- and eighth-grade students at BFMS participated in two environmental monitoring projects within their local watershed: a macroinvertebrate study and a water quality study.

Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the remainder of this project has been cancelled for the health and safety of students, teachers, and NEEF staff. Planned activities had included learning about non-source point pollution and collecting additional samples and data from the field, as well as a tour of the local water utility. The project would then conclude with students reporting their findings to the county parks and recreation department.

What is inquiry-based education? Is it just about asking questions?

Inquiry-based learning does kind of revolve around questions. In addition to that, there are a lot of other structured learning systems—problem-based learning, project-based learning—with all kinds of overlap. But inquiry-based learning doesn't only take place in the classroom. For many of our students, we moved the classroom from a structured place with four walls and windows to a place where they can actually entertain those questions.

The teachers are able to facilitate inquiry-based education, and it can also be facilitated by students or someone else. But the structure of learning is certainly different in that the responses to those questions aren't coming from a textbook, but from their experiences in the field.

During our Greening STEM project at Teaneck Creek Conservancy, for the questions that were being posed, the answers were at the feet of the students. They were in the trees. They were in the creek. The students had to actually dig for those answers, which makes it more engaging.

It's not like they can flip to a page and see that the answer to a question being posed is on page 35. It takes some collaboration. It takes some searching. They would have to probe further, and even question each other and debate whether or not the things they're finding answer the question that was posed.

In your opinion, why is inquiry-based education important?

Two of the most controversial terms in education are “rigor” and “engagement.” How do you measure rigor? How do you measure student engagement? Inquiry-based education is important in that it increases rigor. I think that's undeniable. It increases rigor and the level of engagement is also intensified as students are using their hands and engaging themselves in learning that is authentic and personal. These are the attributes of authentic engagement.

There's a great article by Martin Haberman that talks about the pedagogy of poverty. In that article, he talks about how we used to learn versus how we can learn—and with the 21st century learners that we have before us today, we have to make certain that we are presenting new ways for them to learn.

This is what was taking place when we were at Teaneck Creek. Students had their feet in the water, getting wet and dirty, and I think it made for an amazing learning experience for them. Because of this increased engagement, it increased interest among the learners. They're not just learning about something in a textbook that's being taught through direct instruction.

Inquiry-based education leads to more questions, discussions, and learning that becomes almost student-centered. The students are leading some of the teaching themselves. Inquiry-based education is powerful in that way—it can transform students into teachers.

You have been an educator for over 20 years. What strategies have you found for getting kids to take an active role in their education?

For years I worked with a program called Close Up DC. I was a history teacher, and one of the best places you can teach history and civics is Washington, DC. Every year, we took a group of about seven or eight students to Washington, DC, and we learned about government by visiting the Capitol, the Supreme Court, and the White House. We learned about Theodore Roosevelt at the park that's named in his honor. We learned about World War II at the World War II Memorial.

Whether it's math, social studies, science, or language arts, you can transform the learning experience just by moving the site. It doesn't have to be done every day, but certainly if these opportunities presented themselves a few times during the academic year, I would argue that students will look forward to being in that class because they know that experience is going to occur a few times a year.

You really can't teach passion, but students can certainly become passionate about their work. Whether they are middle school students, high school students, or students that decide to go off into college, [through the Greening STEM approach] we're creating an environmentalist. We're creating students who may want to become scientists. For our purpose it was Teaneck Creek, but another student may want to look at the Hudson River, someone may want to look at the ocean and the pollution from ships that travel overseas.

It's about taking something small and providing a path for a student to expand on that passion, and it can become a serious vocation for many of them.

What initially interested you in NEEF's Greening STEM program at Teaneck Creek?

I was taught very early in my career that you have to be efficacious. You have to work with what you have. When you build partnerships, then you have access to people who have the resources and experience that will expand the work that you want to do.

When I arrived in Teaneck, I came in thinking about what organizations I can partner with in and around this community to help me with my work as an instructional leader. I was very interested in the work that Teaneck Creek Conservancy was doing. Therefore, the relationship started via a mutual investment in children. This relationship expanded with the assistance of a group of amazing teachers from Benjamin Franklin Middle School—specifically Mrs. Jessie Gorant and Ms. Stephanie Paz. They helped make this an amazing collaborative effort.

One of the most amazing parts of this partnership that we created with NEEF, Samsung, Teaneck Creek Conservancy, and Teaneck Public Schools—specifically Benjamin Franklin Middle School—is that the project was in the Teaneck area, providing easy access to our students. Whether you're dealing with pollution or preserving public space, these problems are personal for students who live in this community.

To understand the importance of [for example] preventing noise pollution and preserving natural life, the students have to go out and see and understand what's going on in their backyard. Because it starts with a problem, it increases the level of interest.

Whether it's Samsung, NEEF, or Teaneck Public Schools, we're always looking for ways that we can further engage students—how we can remove them from the classroom to expand their learning experiences.

You have mentored many young people in your time as an educator. How important is the Greening STEM approach in encouraging students to pursue careers in STEM?

If you've ever dissected a worm in science class, the worms were purchased, they were sent to the school, you prepared them in the labs and did that work right there. Imagine that versus going to a place, digging up worms, finding worms, setting up a table, putting on your gloves and doing it on site somewhere else. It makes all the difference.

We work hard to make certain that our classroom spaces at BFMS facilitate this type of learning. But if you have an opportunity to transform the classroom or to move the classroom off-site, you have an opportunity to increase engagement and to make certain that the level of rigor is also increased as well.

The students who were at the creek, they were moving rocks, digging under rocks, grabbing water samples with nets. And they were able to see some of the living organisms they were just learning about. If you're in a classroom, you have to imagine what it looks like versus seeing it in real life, so it really transferred that level of information.

Instead of “this is something that my teacher's telling me, which is something that a book told my teacher, which is something that a publisher provided through the book,” it's me as a student seeing it for myself.

As a teacher, that's the best part of this work—when you produce those “aha!” moments.

Would you recommend other schools participate in a Greening STEM project like this one?

I would recommend it to schools at the university level, college level, high school level, middle school level, and elementary school level. I would even say as early as kindergarten when students first begin learning very foundational information about pollution, not littering, preserving life, and protecting the planet. I think there's a place at every point in our curriculum in the United States where students can learn about the environment and Greening STEM.

Every place you go—every school, every community—has parks. If you have parks, you're going to find some trees. You're going to find some bushes. If you're lucky, you may find some water. Sadly, you may find some pollution. But in it all, you will find a classroom.

If we can secure that park and make it a safe place for students to learn—through the Greening STEM curriculum offered by NEEF—then you find an amazing learning experience where we can take students out of the classroom and into a place where they can engage themselves in inquiry-based learning.

The level of excitement from BFMS students around it . . . I can't speak enough about how valuable that is. It's something I think students will look forward to and something they will always remember, and will have a lasting impression on them as they move on in school, college, their careers and their lives.