The weather plays a crucial role in shaping the flavors and availability of our holiday meals. Whether it's the resilience of wild turkeys against harsh winters or the growth cycle of the apples in your pie, environmental conditions influence everything on your family’s dinner table. Before you dig in this holiday season, delve into the fascinating relationship between our festive foods and the weather patterns that nurture them.

Wild Turkeys' Resilience

Before we gather around the dinner table, let’s consider the wild turkeys that roam across the varied climates of the United States, showcasing their remarkable resilience.

While these large, plump birds can fly and swim for short distances, they are not a migratory species and can be found living year-round in every state in the US except for Alaska. Look for them in open forests where they spend their nights roosting high in the trees, either as part of a flock or individually. Turkey populations living near residential areas have been known to roost on railings, roofs, and even on vehicles!

Wild turkeys live in some of the chilliest parts of the United States, including the Midwest and Northeast, and are able to survive in sub-zero temperatures. As a matter of fact, during spells of severe weather, turkeys can settle in roosting areas without food for up to two weeks, even if they lose up to 40% of their body weight!

The bigger winter challenge for wild turkeys is snowy weather. Wild turkeys eat all sorts of ground forage, including seeds, grains, and small bits of vegetation, but they generally cannot reach foods under more than six inches of snow. Soft, powdery snow also makes it harder for turkeys to move around—the birds will generally “wait it out” in roosts until snow crusts over or melts.

Despite extreme weather, most wild turkeys make it through winter. Survival rates during mild or average winters are between 70 and 100%; harsher winter survival rates are between 55 and 60%. Even during harsh winters, more than enough turkeys survive to maintain healthy breeding populations.

The enduring presence of wild turkeys through harsh climates and sparse winters is a powerful example of nature's resilience, mirroring the ecological balances necessary for wildlife survival.

Climate is Crucial for Cranberries

On the other hand, cranberries—a staple of holiday feasts—rely on the specific climatic conditions of their growing regions, from the intensity of sunlight to the precise temperature levels.

Most of the world's cranberries are produced in the United States, predominantly in Wisconsin, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Oregon, and Washington. The USDA forecasts that the United States will produce 8.24 million barrels of cranberries in 2024, a 2% increase from 2023.

These fruits thrive in a special type of wetland called a bog, which is made up of acidic waters and alternating layers of sand and decomposing plant material. Cranberries grow in man-made wetlands on long, woody vines, which form a thick mat over the surface of the bed. The cranberries harvested from these vines are affected by their local weather conditions.

Cranberries are typically harvested from September to November, and the amount of sunlight the plants receive in the year prior to the harvest can have a big impact on their yield. Greater amounts of sunlight, especially in the fall and winter months, can lead to an increase in photosynthetic activity, producing stronger flower buds and larger berries at harvest time.

This seasonal favorite is restricted to areas that have moderate summer temperatures, with a July daily average maximum temperature of 85°F. Currently, this temperature range restricts cranberry habitat to only as far south as New Jersey, but temperature increases due to climate change may shift this boundary northward. This shift in the fruit's habitat would mean that cranberries, currently the third largest agricultural commodity in Massachusetts, would no longer grow in the southeastern part of that state.

Cranberries rely on regular rainfall during the May through August growing season for large harvests, but the effect of precipitation on cranberry yield can start as early as the previous year's harvest time. Cranberry bogs are flooded with water every winter, and the resultant ice sheet insulates the plant's buds, protecting them as they sit dormant until the spring thaw. If there is insufficient precipitation before the plants enter dormancy, there may be less fruit production the following year.

The delicate balance of weather conditions that cranberries depend on underscores the importance of adaptive agriculture in ensuring the continuation of these traditional harvests.

Pumpkins Battle the Elements

Pumpkins, symbols of autumn celebrations, face a range of weather challenges that can affect everything from their growth to the festive colors they bring to our tables.

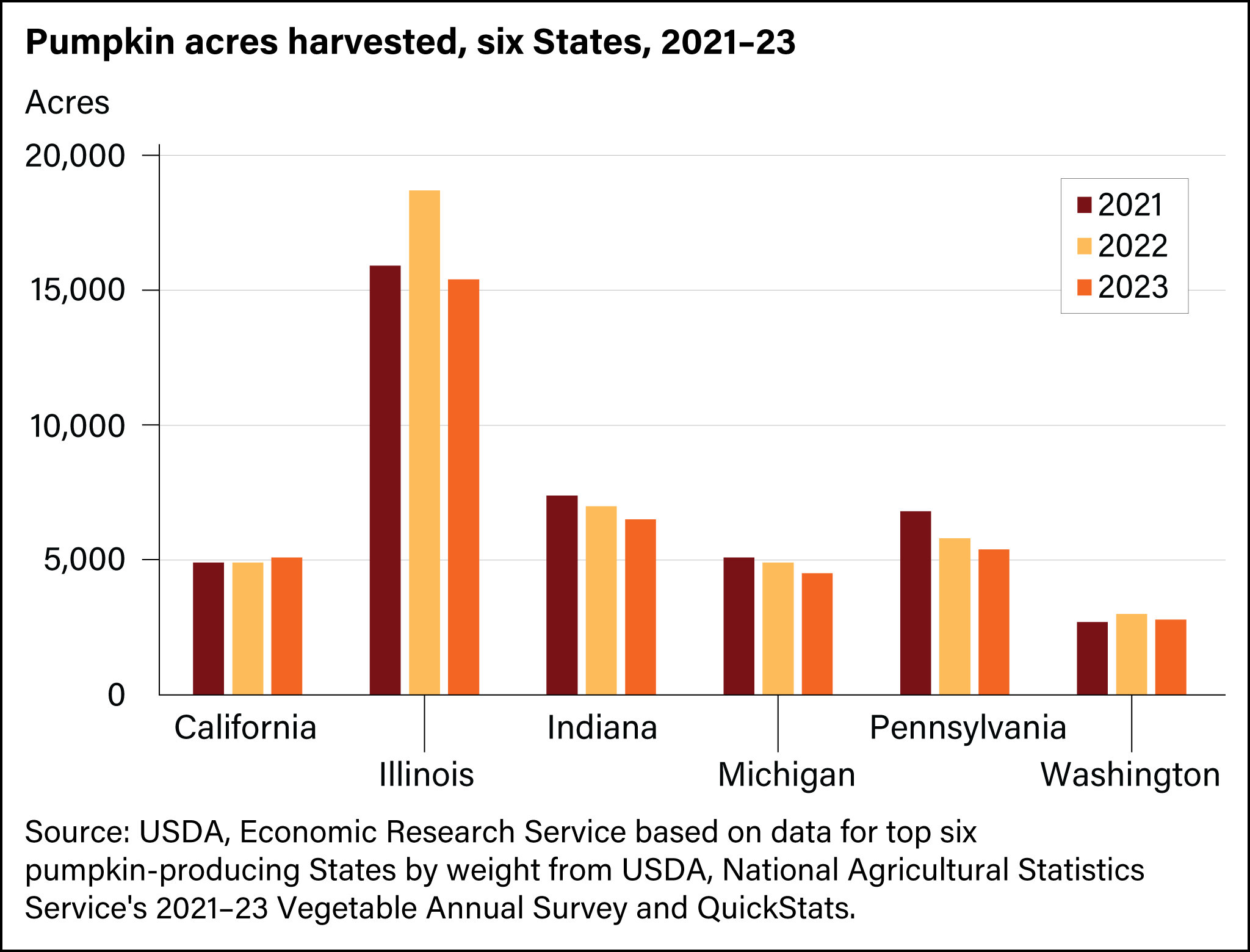

About 80% of the United States' pumpkin supply is available in October, but pumpkin makes an appearance year-round in pies, breads and other foods. All US states produce some pumpkins, but there are six states that produce the most. According to the USDA Census of Agriculture, in 2022, about 45% of pumpkin acres were harvested in Illinois, California, Indiana, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Washington.

Since the majority of pumpkins are grown in these states, the weather in these areas can significantly impact the yearly pumpkin harvest. In 2023, farmers in the top pumpkin-producing US states harvested over 1.2 billion pounds of pumpkins combined.

Too much rain can cause crops to rot and make them more susceptible to infection and disease. Fungi, which thrive in wet conditions, can damage leaves and stems or kill pumpkin vines and fruits.

Dry, hot weather can cause pumpkins to have too many male blossoms and too few female blossoms, resulting in a smaller harvest. Lack of water during droughts can also result in smaller and lighter pumpkins.

Apples Weather Seasonal Changes

Apples, essential to autumn's charm, undergo a rigorous test of endurance against the changing seasons, each phase of weather leaving its mark on the harvest.

Most apples in the United States are grown in Washington, New York, and Michigan. The life cycle and health of this fall staple is directly related to seasons and weather.

Pollination occurs in late spring, and the flowers bloom from mid-April to early June, depending on the growing region.

In the summer, the apple crop can be damaged by heat stress and drought, which can negatively impact the quality of the apples if the orchards are not adequately irrigated. Apple growers might also prune the trees to encourage fruit growth—if the trees are shaded, restricting their photosynthesis, fruit production can drop significantly.

By the end of the summer, apples complete their growth period and begin to ripen. Months of intense light exposure coupled with the arrival of cool nights spurs the activity of a particular enzyme in red apples that generates a red pigment, causing their color to deepen. After the harvest ends, farmers prepare the orchards for winter.

Flower and leaf buds appear on apple trees in late fall and the trees lie dormant throughout winter. In mid-winter, some farmers prune the trees so they will receive plenty of winter sunlight and their foliage and flowers will be healthy, full, and productive the next spring. These cold winter temperatures are necessary to make the apple trees flower, and this requirement restricts the apples' growth to the upper latitudes.

Under climate change projections, this crisp favorite may be at risk—apples rely on cool winter temperatures for flowering, and historically, the harvest following a warmer winter produces a reduced fruit yield and poor fruit quality. Climate change may already be impacting these fruits—over the past 30 to 40 years, the spring bloom dates for apples grown in New York have occurred several days earlier than they have historically. This earlier bloom can lead to increased frost damage, as the trees leaf out and flower earlier in the spring when the temperatures are still variable, potentially exposing young shoots and buds to dangerous chill and threatening the state's $286 million apple industry.

The intricate dance of apples with the weather, from bloom to harvest, offers insights into how even small climatic shifts can have profound effects on agricultural outputs.

Sweet Potatoes Seek Warmth

The sweet potato originated in the Western Hemisphere, where it has become a staple of a nutritious diet in many countries. In the United States, sweet potatoes are predominantly grown in North Carolina, California, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Florida.

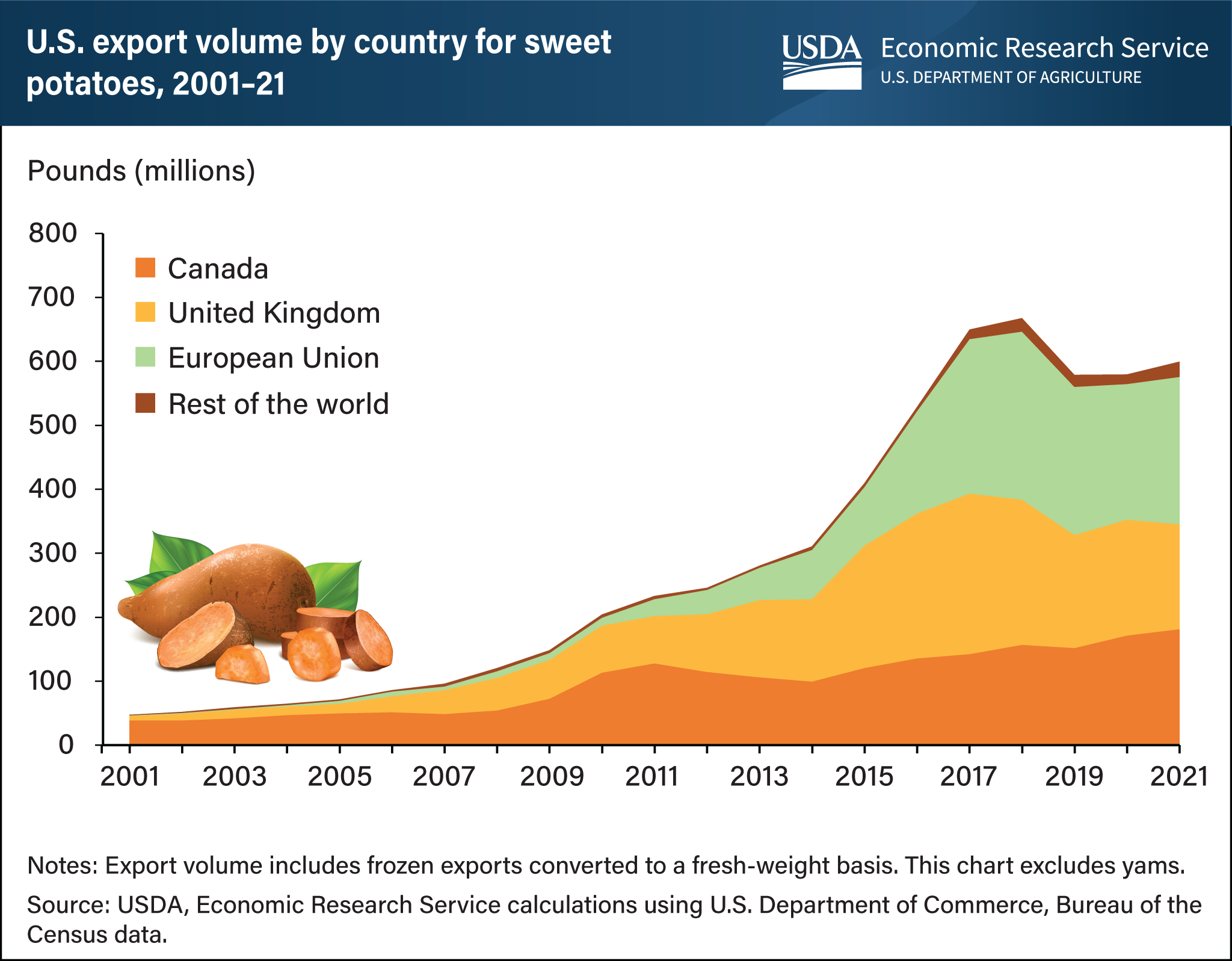

The US is a leading exporter of sweet potatoes, ranking as the top exporter in 2020. From 2001 to 2021, US sweet potato exports surged by 1,157% on a fresh-weight basis, with the export value escalating from $14 million to $187 million over the same period.

Sweet potatoes thrive in warmer weather, needing a long frost-free season to reach full maturity. Frost can damage sweet potato vines and roots. Cold soils, from 55°F and below, can reduce the vegetable's ability to keep well in storage after harvest.

Heavy rains can prevent sweet potato roots from forming properly or may cause the potatoes to split.

The growth of sweet potatoes in optimal conditions showcases the impact of a volatile climate on the production of this nutritious native food.

Vintner's Challenge: Crafting Wine in Changing Climates

What’s better to pair with a rich holiday meal than a fine glass of wine? Vintners, or wine producers, face their share of challenges with a changing climate when attempting to control the cultivation and character of the wine they make.

In the United States, a large portion of the grapes grown to produce wine come from California, Oregon, and New York. The growth and health of wine grapes and the quality of wine are affected by many different weather conditions.

- Sun: White and red grapes that receive a lot of sun exposure generally result in fuller-bodied wines.

- Wind: Too much wind can damage grape vines, reducing crop yield or halting grape maturation. Some wind is necessary, however, to dry out the grapevines and prevent fungal diseases.

- Rain: Grape vines generally need about 22 inches of rain per year to survive. However, too much rain during the summer can cause mildew growth, damaging crops. Excess rain shortly before grape harvest can also affect a finished wine by reducing the amount of sugar in the grapes.

- Frost: Frosts that occur in the spring after the buds have sprouted can kill emerging shoots, while fall frosts can lead to the death of the vine canopy and stop fruit from ripening.

As each bottle of wine is uncorked, it brings with it a story of resilience and adaptation to the climate, underscoring the profound connection between our environment and the flavors we celebrate with during the holidays.

The Impact of Environmental Factors on Food Health

The foods we savor during the holiday season reflect not only our traditions but also the health of the environments from which they originate. As these cherished meals mirror ecological well-being, they also serve as a barometer for the broader impacts of climate on our food systems.

The impact of weather on agriculture directly affects our plates and health. For example, crops stressed by drought or excessive rainfall often have diminished nutritional quality, illustrating the need for sustainable agricultural practices.

Moreover, erratic weather patterns may necessitate increased use of pesticides to manage unexpected pest outbreaks, leading to higher food residue levels. This situation highlights why it's crucial to understand the link between agriculture and health, empowering consumers to make choices that support both personal health and environmental wellness.

Embrace Sustainability This Holiday Season with These Resources

As we revel in the festivities and enjoy our holiday meals, it's crucial to remember that these culinary delights reflect the health of our planet. Each dish serves as a reminder of the environmental impact behind our agricultural practices.

By choosing to support sustainable farming practices and reducing waste, we not only enhance our health but also contribute to the preservation of our environment. Let's commit to making choices that help sustain these traditions and the world around us. Choose sustainability to ensure that these traditions can continue to flourish for generations to come.

Here are some actions you can take to have a more sustainable holiday season:

- Reducing Holiday Waste: Discover the impact of food waste, which comprises 24% of US landfills, and learn strategies to reduce your waste footprint during the holidays and beyond.

- Start a Community Garden to Grow Healthy Food and New Neighborhood Connections: Learn from Chicago’s Loomis Street Community Garden how community gardens can enhance access to healthy food and strengthen community bonds.

- Engineering a Sustainable World Educator Toolkit: Access free lesson plans and resources designed for educators to teach engineering concepts through a sustainability lens.

- Hands-on Activities You Can Do (at Home and at Work) to Help the Environment: Explore practical, hands-on sustainability actions that can be implemented both at home and in the workplace, from energy efficiency improvements to waste reduction.